|

Click on the topic group name to jump to each topic.

Amphibians

Vermont Nature NewsAmphibiansWood Frog

|

Two Closely Related Frog Species of Spring:Spring Peeper - Pseudacris crucifer Our smallest frog species, adult Spring Peepers measure 3/4" - 1 3/8". They vary in color - tan, gray, brown - and have a more or less clear wide "x" on the back which is the source of the species' designation 'crucifer' or cross. Their preferred habitat for breeding is wooded areas near permanent or temporarily flooded ponds and swamps where they congregate in large numbers and sing all night, a chorus that many people associate with the change of season from early to late Spring. A single peeper has a high-pitched ascending whistle which various males sing on different pitches and at different levels of volume. As numbers of frogs build to hundreds at even a tiny vernal pool, the night chorus produced by Spring Peepers sounds like jingling bells with dissonant tones and pulsing synchrony as they sing in and out of phase. Males augment their sound by inflating their throat skin and produce sound that is remarkably loud for the size of the animal. Males sing from trees and shrubs that are in standing water or close to water. Peepers have enlarged discs on the toes that act like suction cups and allow them to climb. Females are attracted to the vigor of the male's song - its volume and frequency. It is estimated that the energy that a frog expends singing all night is about ten times the level of energy expended at rest or about the same as a human running. (So when you lie awake at night listening to the grand chorus, remember that the frogs are doing the equivalent of long distance running.) After mating, females lay eggs singly or in short strings attached to vegetation well below the surface of the water. Tadpoles mature and metamorphose into adults in July and leave the pools and disperse throughout moist woodlands, marshy wet woods, second growth woodlots, sphagnum bogs and non-wooded lowlands near ponds and swamps. Peepers are seldom seen because of their cryptic color and small size. It is interesting to note that in the north Spring Peepers breed from March to June when warm rains arrive, but in the south Spring Peepers breed from November - March when cool rains arrive. It just happens that the temperature of Spring rains in the north corresponds to Fall rains in the south. |

Gray Treefrog - Hyla versicolor Gray Treefrogs grow to 1 1/4" - 2 3/8" and are camouflage-colored to match their environment - greenish to brownish gray with dark blotches on the back. Usually visible is a dark outlined white patch below the eye. Often not seen unless the frog moves is a bright yellow wash on the inner thigh. Gray Treefrogs breed where there are trees and shrubs in or near permanent water. Males give a slow pulsing trill in late Spring and are often heard in the same setting as a chorus of Spring Peepers. Their large toe pads are characteristic of all Treefrogs. Females lay eggs in packets of 10 - 40 loosely attached to vegetation on the surface of shallow water. Gray Treefrogs can be heard giving single notes throughout the summer months on humid days and just before thunderstorms. Tadpoles mature in September. Gray Treefrogs are occasionally seen at the edge of ponds during the breeding season. When they are in trees they are very difficult to spot because of their perfect coloring that matches their environment. One summer day at Bear Paw Pond, what appeared to be a bit of lichen-colored rock took the shape of a frog, moved a few steps and stopped. The lichen-covered rock was indeed a Gray Treefrog. Both Spring Peepers and Gray Treefrogs have the winter survival strategy of being able to gradually lower their metabolic rates and slowly freeze solid in the same manner as the Wood Frog. - Deborah Benjamin |

BirdsBarred Owl Strix varia The Barred Owl, Strix varia, is a large owl of extensive woodlands and is a common year-round resident throughout Vermont. RangeIn North America, it is a widespread resident east of the Great Plains from southern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico and Florida. It also ranges from southeastern Alaska southward to northern California and Idaho and across central Canada. Recently, it has expanded its range westward and, where its new range overlaps with its close relative, the Northern Spotted Owl, hybridization has occurred. A few isolated populations occur in southern Mexico. Physical DescriptionBarred Owls are 17 - 20 inches long with a wingspan that measures from 39 - 43 inches and weigh 14 - 37 ounces. They have a large round head lacking ear tufts and have dark brown eyes. The colors of a Barred Owl include several shades of brown, gray, tan and pale yellow. This owl takes its name from the horizontal banding, called barring, of the ruff of feathers on the neck and upper breast. Below the ruff, the front is broadly streaked vertically. The back is brown dotted with rows of white spots. The facial disk is strongly outlined in dark gray. The beak is a bone yellow color and the scales of the feet are golden tan. Males and females are similar in plumage. The overall appearance is a large owl that blends well into its habitat. Habitat & FoodBarred Owls prefer woodlands that contain large trees with cavities for nesting and open areas with wetlands or riparian areas for hunting. Adults pair for life and will nest in a cavity of a large tree, typically elm, beech or maple; occasionally, they will use an abandoned crow or hawk nest. They exhibit territory and nest site tenacity and will reuse the same nest as long as it serviceable. In Winter, males range further from a territory while females stay closer to home and defend the territory. Barred Owls are generalists in their choice of prey and feed on small mammals, including mice, voles and squirrels, as well as reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. They are nocturnal to semi-nocturnal and will often drop down from a branch to pounce on prey. This technique allows them to hunt in fairly dense cover. ReproductionBarred Owls in Vermont begin their breeding season in late February or March. Their loud, rhythmic calling announces the onset of nesting and may be heard throughout the breeding season and well into the summer months. Their hooting has been described as: "Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-all?" Males and females will often call in duets. The female's call ends in a vibrant drawn-out tremolo; the male's call is lower in pitch and ends abruptly.  NestlingsThe female lays 2 to 3 pure white eggs and incubation, which begins as soon as the first egg is laid, lasts for 28 - 33 days. Nestlings, covered in white down, open their eyes at about 1 week and are brooded continuously for three weeks. At 4 - 5 weeks of age, their natal down has given way to soft brown, gray and tan and they start to look like an owl. At this age, they will walk out of the nest onto nearby branches and beg loudly for food through beak clapping, hissing and screeching. They fledge at 6 weeks and continue to receive food from their parents up to 4 months of age. Habitat:Barred Owls prefer woodlands that contain large trees with cavities for nesting and open areas with wetlands or riparian areas for hunting. Wildlife Observation Tips:Listen for their distinctive hooting which has been described as: "Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-all?" Males and females will often call in duets.  Recommended Reading

- Deborah Benjamin |

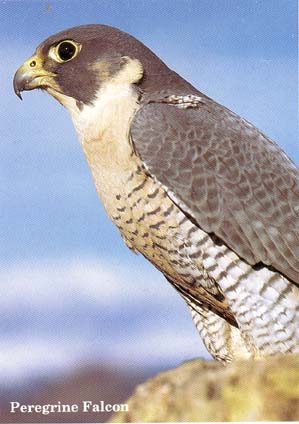

Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus Peregrine Falcons have been observed in Hazen's Notch for the last few years. This Spring a pair of birds has been observed but no nest site has been located. Peregrines have made an impressive comeback in Vermont in the last 20 years after having been extirpated from the United States east of the Mississippi River by 1965. Their decline was directly due to the deliterious effects of DDT, a pesticide that was commonly used to control mosquitoes in residential areas. Peregrines are animals at the top of the food web; they hunt and eat birds. By eating Red-winged Blackbirds, Pigeons, Robins and other species, Peregrine falcons accumulated high levels of DDT in the fat tissues. This caused female Peregrine falcons to lay eggs with shells that weretoo thin to survive incubation. DDT was finally banned in 1972. A captive breeding program was initiated by Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology in 1975 using techniques refined by falconers who raised the birds for sport. 93 chicks were raised in captivity and released (hacked) into the wild in Vermont from 1982 - 1987. A pair of Peregrines nested successfully on the cliffs of Mt. Pisgah at Lake Willoughby in 1985. This was the first pair to nest in the wild in Vermont for nearly 30 years. The number of breeding pairs rose steadily throughout Vermont on suitable sites that historically attracted birds. Peregrines nest on narrow ledges on steep cliff faces that are inaccessible to predators. Biologists at the Vermont Institute of Natural Sciences made an assessment in 1995 of current and historical locations where the habitat was still suitable for peregrine falcons. They determined that 9 historical sites that had not previously been recolonized have high potential to attract Peregrine falcons. The cliffs of Sugarloaf Mountain in Hazen's Notch are one of the nine sites. This Spring a territorial pair of unbanded falcons was observed flying in the skies over Hazen's Notch. This is not the first year that Peregrine falcons have been seen in Hazen's Notch. However, no peregrines have nested in Hazen's Notch to date. 29 territorial pairs of Peregrine falcons occupied cliffs around the state in 2003 including several newly established territories. That year 16 pairs succeeded in fledging at least 39 chicks. We will continue to look for these magnificent birds and hope that in the near future, the cliffs in Hazen's Notch will host a family of falcons. Wildlife Observation TipsIf you know that Peregrines are nesting in an area, you should view them from a distance using binoculars or a spotting scope so as not to disturb the birds. Hiking Trails where nests are active are closed by the state during the nesting season, as the birds especially do not like to be disturbed by people or animals that they can see at the tops of cliffs above the nest site.  Recommended Reading

|

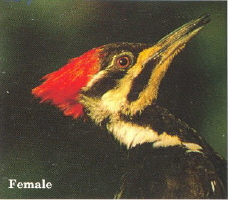

Pileated Woodpecker Dryocopus pileatus The Pileated Woodpecker is our largest woodpecker with a body length of 16" - 19", a weight of 9 ounces - 12.5 ounces, and a wingspan of 26" - 30". There is a distinct difference of color between the adults: the male has a red crest and forehead and has red in its black mustache stripe; the female has a red crest and a gray to yellow-brown forehead and no red in the mustache stripe. Male Pileated Woodpecker |

Pileated Woodpecker pairs remain year-round on their breeding territory. Within the last two weeks, the call, a loud and long "kuk-kuk-kuk-kuk-kuk-kuk" can be heard as the breeding season begins. At this time of the year, before the leaves are out, one can observe the woodpecker by listening for the call and by looking at large, old maple trees. Male Pileated Woodpecker above |

Pileated Woodpeckers make large rounded rectangular excavations on old trees in search of their favorite foods: carpenter ants & wood boring beetle larvae. Later they will excavate roundish holes in which to raise their young. Their holes persist for a long time & present nesting & roosting opportunities for many birds & mammals: American Kestrel, Saw-whet Owl, Raccoon, & Flying Squirrel. Female Pileated Woodpecker above Pileated Woodpecker "Cavity" in Sugar Maple - below.  For More InformationHabitatPileated Woodpeckers are found in mixed deciduous and coniferous forests where there are large trees. Large excavated cavities in older trees indicate the presence of Pileated Woodpeckers. Their cavities are visible for many years. A pair will defend its territory year-round and will remain in a general location for many years, as long as they can find food and nesting opportunities. Wildlife Observation TipsA large pile of wood chips at the base of a tree indicates a recent visit for feeding. Their calls ring loud and can be heard from as far as 1/2 mile away.  Recommended Reading

|

PlantsMosses and Lichens

|

False Hellebore

|

Juneberry

|

MammalsBlack Bear

|

Moose - Alces alces americanaHistoryMoose are the largest members of the deer family. They live in the northern forest regions of North America, Europe and Russia. The earliest known drawings of moose are from the stone-age in the Ussuri Valley on the Russian/Chinese border near the Sea of Japan. Moose migrated west to northern Europe and eventually east to North America across the Bering Land Bridge that linked Siberia to Alaska approximately 100,000 years ago during the Pleistocene Epoch. They then spread across Alaska, south into the upper Midwest, and eastward through Canada and the northern United States. The name 'moose' comes from the Algonquin word 'one who strips or eats off' which is a reference to the animal's diet of twigs and leaves stripped from branches. Four Sub-speciesThere are currently four sub-species of moose in North America (of the 7 sub-species worldwide). The Eastern Moose, Alces alces americana, occurs in eastern Canada and New Brunswick to eastern Ontario and south to Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and New York. The Northwestern Moose, Alces alces andersoni, ranges from northern Michigan and Minnesota and western Ontario to central British Columbia and north to eastern Yukon. The Shiras Moose, Alces alces shirasi, occurs in northwestern Wyoming, Montana and northeastern Idaho to southern Alberta and southeastern British Columbia. The Alaskan Moose, Alces alces gigas, occurs in Alaska and is 30% larger than the other 3 sub-species. Habitat/DietIn Vermont, moose occur in greatest numbers in the Northeast Kingdom and in the Green Mountains. They live in extensive forested areas that contain wetlands surrounding lakes, ponds, and bogs which supply a variety of food sources. In Summer, they feed on the twigs, leaves and bark of willow, aspen, red maple, striped maple (commonly referred to as "moosewood"), paper birch, beaked hazelnut, and red-osier dogwood; and the roots and leaves of aquatic plants, including water shield, yellow pond lily and several pondweeds. In Winter, their diet is more restricted to conifer (balsam fir primarily) and hardwood twigs. A home range for a moose is a radius of two to ten miles if there is an adequate food supply and Winter shelter. SizeMoose are the largest mammals in our landscape and have little to fear from other animals. Even where their range overlaps that of the wolf, only young and weak moose are typically taken by predators. A mature moose armed with sharp hooves and a powerful kick inspire respect from a pack of wolves. Bull moose in prime condition reach a weight of 1,200 - 1,600 pounds; mature cows reach a weight of 800 - 1,300 pounds. They stand six feet tall at the withers and measure nine feet from nose to tail. The legs are very long to facilitate a high-stepping gait through tangled vegetation and deep water. Moose live on average 16 years with cows sometimes reaching 20 years of age. Brain ParasiteThe greatest challenge to moose is survival during Winter and escape from parasites. White-tailed deer carry a brain parasite that does not cause illness in the deer, but passes out through its feces and is eaten by snails. The infected snails are in turn inadvertently eaten by moose grazing on the wet vegetation that the snails live on during the day. The moose develops 'brain sickness', looses vigor, becomes paralyzed or blind, and can die from the infection. Moose are also bothered by ticks which can reach very high numbers especially in Winter when moose do not have the benefit of a Summer wallow in mud or a respite from heat and biting flies by standing shoulder deep in water. Irritation, scratching, infection and hair loss can severely weaken a moose with ticks in Winter. Spring and SummerVernal MigrationWith the arrival of Spring and the first signs of greening vegetation, moose leave their Winter quarters at middle and higher elevations and return to their favorite places in wetlands and in the woods surrounding wetlands. In May, moose might be seen eating the succulent grasses in roadside ditches. It is believed that they are attracted to the accumulation of road salt in runoff water in the ditches. Moose CalvesCows and their yearling young have spent the Winter together. As the female moose prepares to give birth to her new young, she will drive her adolescent young away. At first confused by the rebuff, the yearling(s) will stay in the vicinity of the mother, but she will not allow one to approach. Moose are born in Vermont from mid-May to early June. Twins are born to mature cows 15% - 75% of the time. Newborn calves weigh 28 - 35 pounds. They will double their weight in 3 weeks from rich milk and forage. Their coat is a light golden-brown and does not have spots for concealment (like the white-tailed deer fawn). A calf's defense is in its mother's vigilance and swift response to any perceived danger which she dispatches through charging and thrashing with her hooves. "A moose calf's bond to its mother is survival. In time, the calf responds as if a shadow. If the cow looks behind with ears erect, so does the calf." [Seasons of the Moose, p. 75] Within five months, new calves weigh over 300 pounds. Moose BullsBulls feed intensively (as much as 50 pounds/day) in Spring on fresh grasses and aquatic vegetation (which is rich in sodium that is stored in large quantities in the rumen) to replenish their low levels of protein and fat and to nourish the rapid growth of new antlers. Peak antler growth corresponds with the longest days and, with a total spread of 4 feet by late Summer, their antlers grow by as much as 1 ½" per day. First to grow is the stout horizontal antler beam which supports the large palm-shaped portions from which grow the upwardly pointing tines. During growth, the antlers are fed by a blood rich covering of skin called velvet at which time the antlers are delicate and easily damaged. By the time the antlers are fully grown, the bone hardens and the velvet abates, cutting off the blood supply; a bull will thrash against vegetation to rub off the velvet and to demonstrate to others his potential vigor. A full rack weighs up to 50 pounds. Bulls eat 50% more food in August than is required for basic metabolism to build up strength for the next important season, the rut. This is the time of year that bulls weigh their most; they start to congregate in food rich areas in early September in anticipation of finding and defending females. Fall and WinterBreeding SeasonWith the arrival of cooler temperatures, testosterone levels rise in males and hormones bring on estrus in females; it is the beginning of the breeding season called "the rut". Males patrol a region and establish relationships with one or more females. They scrape wallows into which they urinate. Females will visit the wallow, roll in its musky scent and will defend a wallow from other females. Bulls will deliver throaty hollow grunts and tremendous bellowing to draw attention to their presence. Moose can pivot their ears individually to 180 degrees and have very good hearing. It is believed that the shape and positioning of the antlers with respect to the ears enhances his ability to hear the higher-toned wavering calls of a female from quite a distance. In late September and early October, mating takes place. One bull in prime condition will escort 3 or 4 females. Other younger males will have to wait until they have grown bigger to challenge the senior bulls. A male will raise its head and sample the air near a cow's urine with a special olfactory gland in the palette, a phenomenon called the Flehman Response, that will reveal whether or not the female has ovulated and is receptive to mating. 90% of cow moose will breed each year. Through the breeding season, bulls will expend a great deal of energy challenging other bulls and will loose about 20% of their body weight. Unlike many mammals of the North Woods, male moose enter Winter depleted of energy and fat reserves, weighing 20% less than at the beginning of the rut. Winter SurvivalMoose have a different technique for surviving Winter - heat retention instead of heat production. As snows deepen, they move from lowland wetlands and forest to mid elevations. Their large bulk retards heat loss. Their hollow hairs help trap heat and insulate the body; their black skin color also helps absorb solar radiation. They expend much less energy at this time of the year, instead waiting patiently, sometimes resting for days under an open bowl beneath conifer trees. They will wait and eat twigs within reach of where they lie. Moose are the first members of the deer family to shed their antlers, sometimes as early as November and usually by the end of December. With the lengthening days of late Winter, new antler growth begins and the cycle begins again. - Deborah Benjamin.

|

Bobcat Lynx rufus

|

Small Mammals of Vermontin the Order Insectivora

|

Nature GearEquipment for Observing WildlifeBinocularsThis is the most important piece of equipment for anyone wishing to observe birds and animals at a distance or small animals at close range. Binoculars are described by two numbers separated by an "x". The first number refers to the power of magnification, usually ranging from 6 to 10. Binoculars with high magnification are well suited to viewing distant objects. With this high magnification comes the greater difficulty of locating objects and then following them as they move.  The second number refers to the diameter of the focal opening. This number should ideally be 5 times the first number. The focal opening determines how much light enters the binoculars. A smaller focal opening won't let in enough light for viewing in a dense forest. A nice compromise is to look for binoculars with a 7x35 or 8x40 power. CamerasAlthough there are many inexpensive cameras with a small zoom lens and built-in flash, most of these are inadequate for taking photographs of wildlife. If you hope to have any success with wildlife photography, you should plan to purchase a 35mm single lens reflex (SLR) camera. The two main reasons are the lens and the shutter speed options. Most cameras come with a 50 or 55mm lens which approximates the view one has with the human eye. With this size lens you will be disappointed to see how small objects look in your photographs when they seemed so much bigger through the viewfinder. The small zoom lens on an inexpensive pocket-style camera isn't much better. You will need a 75-200mm zoom lens in order to make most wildlife appear large enough when viewed from a distance that doesn't alarm the subject of your photograph. Automatic focus is an important feature since you may not have time to adjust the focus while keeping your subject properly framed.  The second reason for buying a 35mm camera is the shutter speed options. With wildlife photography you need to be able to "stop" or freeze the movement of your subject. A faster shutter speed (1/250 sec. or 1/500 sec.) will accomplish this. You may also want a sharp focus over a long distance, known as "depth of field", that comes with a smaller lens opening, or "aperture". Only 35mm cameras have this kind of adjustability. In order to have a properly exposed photograph with this smaller aperture and faster shutter speed, you will want to purchase film that is intended for such "fast" settings. This will be a film with an ASA number of 200, rather than the typical 100, 64 or even 25 that is sold for most inexpensive cameras. Hand LensesAnother way to enjoy the natural world is to unlock its secrets in miniature with the aid of a hand lens (or loupe). Flowers, seeds, mosses, insects and the texture of tree bark and stone are fascinating to look at with the aid of a hand lens.  The best hand lenses are made of glass and stainless steel. Hand lenses come in a variety of magnifications.The most useful levels of magnification are 10 x, 14 x, 16 x, and 20 x. As the magnification increases, the depth of field decreases (which means the subject will look more flat than three-dimensional). Also, as the magnification increases, so does the price (from $20.00 - $80.00). Many plastic magnifiers are less expensive and are very good for introducing children to the natural world close-up. Most university bookstores sell hand lenses. A good source of scientific equipment is Carolina Biological Supply Company. (www.carolina.com) They specialize in supplying science educators with materials and equipment. The Ben Meadows Company (www.benmeadows.com) also sells hand lenses and has a larger selection of binoculars. They are an excellent source of equipment for all aspects of natural resources management. - Deborah Benjamin  |